The Ceremony of Tobacco

THE CEREMONY OF TOBACCO©

By Albert ‘Sun’ Butler.

Artwork© by Karen Lynch Harley. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: No part of this article is intended to represent that smoking organic or ceremonial tobacco is any less dangerous to your health than conventional tobacco

“There is in the country an herb which they call tabaco,

which is a kind of plant, the stalk of which is as tall as the chest of a man....and they sow this herb and they keep the seed which it produces to sow the next year and they cure it carefully for the purpose of securing predictions.” From The first to mention ‘tobaco’: Oviedo y Valdés on Venezuela

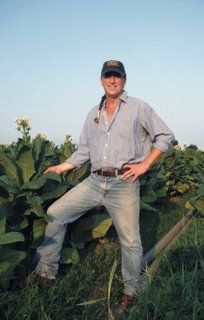

which is a kind of plant, the stalk of which is as tall as the chest of a man....and they sow this herb and they keep the seed which it produces to sow the next year and they cure it carefully for the purpose of securing predictions.” From The first to mention ‘tobaco’: Oviedo y Valdés on VenezuelaIn July the hummingbirds return to our farm in southern Virginia. They come to feast on the nectar of acres of pink and purple trumpet shaped tobacco flowers. Buzzing our heads as we top the tobacco plants, they remind us that according to our Cherokee legends Hummingbird slipped past the greedy Dagul-ku and stole a fertilized bloom of the first tobacco plant to bring back to the People[1].

The history of tobacco or “Uppa-woc”, Native America’s most sacred plant begins with its cultivation along with squash and beans around 5000 BC. By 200 BC the Hopewell Mound culture demonstrated a sophisticated ceremonial culture based on the discovery of more than two hundred stone effigy tobacco pipes at the Ohio mound site. Native only to the Americas, tobacco was introduced to European explorers and settlers by the American Indian tribesman who greeted them. Their first gifts to Columbus and later to the settlers at Jamestown included tobacco. Native Americans taught European settlers to cultivate a treasure trove of

domesticated crops native only to the New World. Exported to Europe, corn, potatoes and sweet potatoes fueled the population explosion and large scale agriculture that made the Industrial Revolution possible. Yet it was a world-wide market for tobacco that drove the developing economic engines of Colonial America.

domesticated crops native only to the New World. Exported to Europe, corn, potatoes and sweet potatoes fueled the population explosion and large scale agriculture that made the Industrial Revolution possible. Yet it was a world-wide market for tobacco that drove the developing economic engines of Colonial America.Many pre-Columbian tribes-people were adept agriculturalists. They grew food crops to supplant their diet of wild plants and game and to sustain their People during lean times. Without draft animals or iron plows, Native American farming was very labor intensive. The devotion of limited human resources to growing a crop such as tobacco that has no food or fiber value indicates that it was very precious. Among the Yanomamo of Brazil the word for ‘being poor’, hori, means literally “without tobacco”.

In the current mass-produced on-demand culture of instant gratification it is difficult to imagine the value of something based upon the hours of labor required of us to produce it. The spiritual observance of “offering up” that which is precious to us has been relegated to the cultural dust-bin of ‘myth and superstition’. So what is it about the tobacco plant that gives it such spiritual significance among Native American peoples? What’s more, are there lessons here for today’s society, addicted not only to nicotine and other drugs, but to excess in every form?

"To the red man," said Assiniboin chief Dan Kennedy in 1939, "the Pipe of Chiefs symbolizes what the Magna Carta and the Ark of the Covenant stand for with other races."

Tobacco is central to Native American prayer ceremony. It

is offered and smoked as a means of communicating with Spirit. Alfred Savinelli’s 1993 treatise ‘Plants of Power’[2] relates, “it is said, that the ancestors remember the pleasure of smoking the leaves and dried blossoms. So they return to partake in the essence of tobacco”. When prayers were made to the Great Spirit, pre-Columbian Indians made offerings with tobacco, the most valuable substance they possessed. The Cherokee consider these offerings to be contracts with the helper spirits that carry our prayers to Creator. Gifting tobacco is a way of showing respect and giving thanks. Above all, tobacco is medicine. It is used in healing ceremonies, teas, poultices, and to pray for good health.

is offered and smoked as a means of communicating with Spirit. Alfred Savinelli’s 1993 treatise ‘Plants of Power’[2] relates, “it is said, that the ancestors remember the pleasure of smoking the leaves and dried blossoms. So they return to partake in the essence of tobacco”. When prayers were made to the Great Spirit, pre-Columbian Indians made offerings with tobacco, the most valuable substance they possessed. The Cherokee consider these offerings to be contracts with the helper spirits that carry our prayers to Creator. Gifting tobacco is a way of showing respect and giving thanks. Above all, tobacco is medicine. It is used in healing ceremonies, teas, poultices, and to pray for good health.Although a few South American and Caribbean tribes chewed tobacco and used snuff habitually, there is little evidence that pre-Columbian Native Americans suffered from addiction to smoking the herb. Only the medicine-men were daily users of tobacco for healing rituals and for communicating with Spirit. Pipe-keepers were required to be of the highest character and moral standards. Tobacco was smoked during official functions such as tribal councils, and when guests visited the lodge. When hunting parties from neighboring tribes met each other in the field, the pipe was smoked among them to demonstrate peaceful intentions.

A warrior seeking vision would pack his bowl with a special smoking mixture supplied by the medicine elder and then carry his pipe into the wilderness to pray for up to four days. During this time he would not drink or eat or smoke but concentrate his full attention on ‘crying-for-a-vision’. Only upon returning to the sweat lodge and relating his experiences to the medicine elder was the pipe smoked in contemplation.

A warrior seeking vision would pack his bowl with a special smoking mixture supplied by the medicine elder and then carry his pipe into the wilderness to pray for up to four days. During this time he would not drink or eat or smoke but concentrate his full attention on ‘crying-for-a-vision’. Only upon returning to the sweat lodge and relating his experiences to the medicine elder was the pipe smoked in contemplation.“According to our way of looking, the world is animate. This is reflected in our language, in which most nouns are animate...Natural things are alive, they have a spirit. Therefore, when we harvest wild rice on our reservation we always offer tobacco to the earth because, when you take something, you must always give thanks to its spirit for giving itself to you.” Winona LaDuke. Resurgence, Sept/Oct, Issue 178, p.8.

Western Science sees plants as biological factories producing novel metabolites and natural compounds that may be useful to us in our quest for a more secure and convenient future. Janiger, M.D., and Marlene Dobkin De Rios, M.D. reported that “Nicotine may affect the concentration of biogenic amines, particularly serotonin, in the brain, which may predispose to changes in consciousness”. Native Americans believe that plants and all living beings are our allies and helpers if we learn to listen to their medicine. Our cosmology personifies the qualities that we observe in plants and animals as spirit helpers.

Thus the wily and adaptable coyote is known as the ‘Trickster’, a powerful teacher. Observing that corn beans and squash grow well together by fertilizing and protecting each other, these diet staples became the ‘Three Sisters’[3], our Sustainers(pictured right). Buffalo Calf Woman changed herself from a buffalo into a woman and brought the Sacred Pipe Ceremony[4] to the Lakota People. This First Pipe is still kept and revered by the People on Pine Ridge Reservation SD. Through these stories Native Americans developed a personal relationship with the natural world and better understood its benefits and dangers.

Thus the wily and adaptable coyote is known as the ‘Trickster’, a powerful teacher. Observing that corn beans and squash grow well together by fertilizing and protecting each other, these diet staples became the ‘Three Sisters’[3], our Sustainers(pictured right). Buffalo Calf Woman changed herself from a buffalo into a woman and brought the Sacred Pipe Ceremony[4] to the Lakota People. This First Pipe is still kept and revered by the People on Pine Ridge Reservation SD. Through these stories Native Americans developed a personal relationship with the natural world and better understood its benefits and dangers.In the Christian faith, wine is so sacred that it is used to represent the blood of Jesus. Tobacco, our most sacred plant is believed to carry the prayers of the People. These ceremonies bring comfort and a sense of one-ness with their Creator to millions of people. Yet, together tobacco and alcohol abuse have killed more Christians and Native Americans alike than all of the Anglo/Indian wars. You may say what you will about the theory of Intelligent Design; I think God is trying to tell us something. Taking that which is Sacred, to use profanely may be hazardous to our health.

The problem with mass-consumerism is that it takes whatever has the highest value and produces huge quantities until it has little value at all. The 2005 documentary ‘Bright Leaf’[5] chronicles producer’s Ross McElwee’s family history as descendants of the man who developed Bull Durham, the first successfully mass marketed tobacco in the 1800s. John Harvey McElwee stunned his genteel neighbors in Statesville NC when he unveiled his plan to begin mass producing cigarettes. James Duke, the founder of American Tobacco Company had the same idea and obtained the secret blend for Bull Durham through some 19th century corporate espionage. The ensuing tobacco war left the McElwees’ warehouses and business burned and their financial empire ruined. The Duke family went on to make a great deal of money from Bull Durham and other tobacco products. This is the history of the first mass-produced cigarette.

Native Americans traditions teach that everything that is alive has a spirit and each living beings qualities are determined by that spirit. We also maintain that when you put ill spirit or bad intentions into something, that negativity can be passed on and cause great harm. That is why we put such emphasis on “doing things in the right way”. The ‘right way’ lies first and foremost in honoring the Sacred. Indigenous peoples make very little distinction between the mundane and the sacred. All tasks and activities that contribute to the survival of the People are sacred no matter how trivial or onerous. Thus good intentions and spirit go into the production of food, material and handiwork on which the tribe depends. This good spirit is passed on from the maker to the end-user when the product is used or consumed resulting in good health and a good hunt, or harvest. What kind of intentions and spirit went into the manufacture of your current brand of tobacco?

Native Americans traditions teach that everything that is alive has a spirit and each living beings qualities are determined by that spirit. We also maintain that when you put ill spirit or bad intentions into something, that negativity can be passed on and cause great harm. That is why we put such emphasis on “doing things in the right way”. The ‘right way’ lies first and foremost in honoring the Sacred. Indigenous peoples make very little distinction between the mundane and the sacred. All tasks and activities that contribute to the survival of the People are sacred no matter how trivial or onerous. Thus good intentions and spirit go into the production of food, material and handiwork on which the tribe depends. This good spirit is passed on from the maker to the end-user when the product is used or consumed resulting in good health and a good hunt, or harvest. What kind of intentions and spirit went into the manufacture of your current brand of tobacco?“Before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water

After enlightenment, chop wood and carry water” – Wu Li, Chinese Zen Master

Author Rick Fields in his seminal book ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’[6] tried to introduce Western readers to the ancient Chinese Zen (and Native American) idea that the performance of simple daily tasks can be a form of relaxing meditation. While we enjoy the benefits of technology, our increasing alienation from the natural world has made it more difficult to maintain a spiritual outlook in our day-to-day. One solution is to go about the simplest and most mundane tasks, especially obtaining and cooking food, using water and fire and maintaining our shelter with prayerful intention. By finding joy and thankful meditation in simple pleasures and even difficult tasks, we open the door on a world of perception where our half-filled glasses may be over-flowed with satisfaction and understanding!

The making of Tobacco is a most sacred aspect of tobacco ceremony. Tobacco leaves are selected, ordered with moisture and cut and blended with herbs to make fragrant smoking mixtures. Each pipe carrier’s mixture is uniquely based on their family’s traditions. For the tobacco aficionado, the experience of enjoying your own blended rag or flake cut from the natural tobacco leaf cannot be equaled with a pack of manufactured cigarettes or pipe tobacco. The tobacco companies have kept the details of tobacco blending secret for over two hundred years refusing to list even the ingredients in their additives. What’s in your tobacco[7]?

My family created Sotoya Ceremonial Tobacco in 2003 to provide certified organically grown tobacco to our friends at Pow-wows that use tobacco in a ceremonial way. Sotoya is a Lakota word for ‘Sacred Smoke’ and we honor that tradition by growing tobacco with prayer and respect and according to ceremonial procedures. In 2005 we added the Grandad’s Tobacco website to introduce our customers to the concept of cutting and blending your own tobacco at home. Grandad’s direct markets certified organic tobacco from other small family growers like ourselves. We believe that introducing our customers to organic traditional whole-leaf tobaccos grown in a good-way will be the first step in re-introducing the present day People of Turtle Island[8] to the respectful use of tobacco in prayer and moderation.

Most Indian peoples felt that smoking together helped to create a spirit of congeniality and cooperation. "See our smoke has now filled the room," said a Delaware Indian from Oklahoma named Jesse Moses to the anthropologist Frank Speck. "First it was in streaks and your smoke and my smoke moved about that way, but now it is all mixed up into one. That is like our minds and spirit too, when we must talk. We are now ready, for we will understand one another better."[9]

For more information on Tobacco Ceremony please visit our website at http://www.sotoyatobacco.com/

Re-prints of this article may be obtained by e-mailing us at sotoyatobacco@yahoo.com

For complete instructions on How To Make-Your-Own Tobacco visit http://www.grandadtobacco.com/

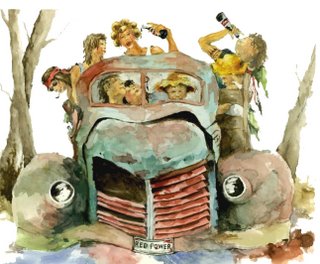

’The Ride Home From Picking Tobacco’(right) and the other paintings which accompany this article are the work of Karen Lynch Harley, Haliwa Saponi artist and owner of Red Earth Gallery. Prints may be ordered at http://redearthgallery.net/

’The Ride Home From Picking Tobacco’(right) and the other paintings which accompany this article are the work of Karen Lynch Harley, Haliwa Saponi artist and owner of Red Earth Gallery. Prints may be ordered at http://redearthgallery.net/[1] Hummingbird Brings Back Tobacco; Cherokee origin legend http://www.sotoyatobacco.com/hummingbird.htm

[2] Plants of Power: Native American Ceremony and the Use of Sacred Plants; By Alfred Savinelli ISBN: 1570671303

[3] The Three Sisters; Iroqouis origin story, http://www.birdclan.org/threesisters.htm

[4] White Buffalo Calf Woman Brings The First Pipe; John Fire Lame Deer 1967 http://www.kstrom.net/isk/arvol/lamedeer.html

The Sacred Pipe ISBN 1567310885 Black Elk Speaks; http://www.ewebtribe.com/NACulture/sacred.htm

[5] http://www.pbs.org/pov/pov2005/brightleaves/about.html

[6] Chop Wood, Carry Water – A Guide to Finding Spiritual Fulfillment in Everyday Life ISBN 0874772095

[7] What’s In Your Tobacco? http://www.grandadtobacco.com/tobacco-additives.htm

[8] Turtle Island; Native American name for the North, Central and South Americas

[9] Encyclopedia of North American Indians; http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/naind/html/na_039200_tobacco.htm